Interview by Ukrainian Olya Zhugan:

I’m looking at the woman, standing in front of me. Her name is the same as mine, Olia, and sharing this makes me feel closer to her. She is probably just a bit younger than I am, in her early thirties but she definitely looks more exhausted, sad or is it frightened. I can’t quite describe what it is I see in her eyes. She is not wearing any make-up, her hair is not done and her dress is a bit wrinkled.

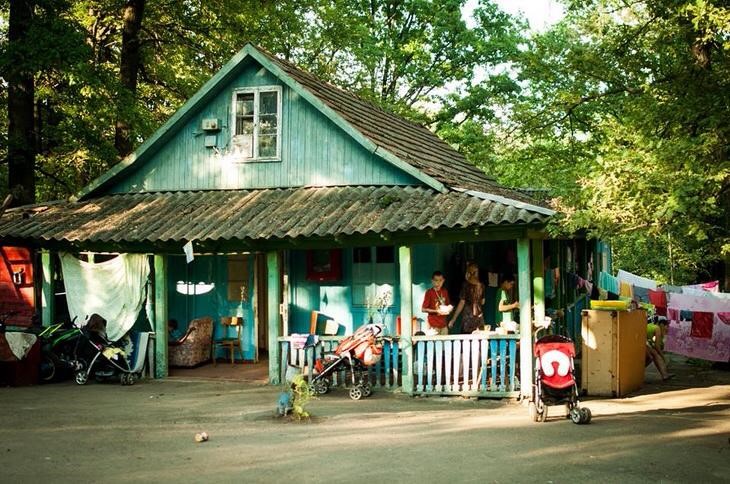

We are standing on a little verandah outside a tiny wooden house. There are about thirty of them, absolutely identical. The houses are set on the edge of the wood. They are quite old and shabby, but surrounded by ancient tall oaks, which makes me think of a fairy-tale. It is the best she do now; an abandoned children’s camp that was provided to the Displaced by the authorities.

We are standing on a little verandah outside a tiny wooden house. There are about thirty of them, absolutely identical. The houses are set on the edge of the wood. They are quite old and shabby, but surrounded by ancient tall oaks, which makes me think of a fairy-tale. It is the best she do now; an abandoned children’s camp that was provided to the Displaced by the authorities.

It is only two weeks since Olia together with many other people arrived at this camp. It lacks most of the things they were used to when living in a modern European city. Now they do not have hot water or heating, and only a few crude stoves for a hundred people. Most of them only took absolutely essential things when they were fleeing — money, documents and some clothes. There was no time or possibility to get a van or a truck and bring what they needed. It was too expensive anyway. Transporting people away from the war has become a business for some people.

“So, how are you getting on? – I ask her.

“It is not that bad,” she replies. “Of course, we had to forget about lots of things, which seemed to be just ordinary things in our everyday life. We do not have an iron, a hairdryer or a microwave. But when you start worrying about what to give your children for lunch or how to keep yourself clean, you stop thinking about such trivial things.

People from the community outside bring a lot of things for us here, from tissues to duvets. I do not know what we’d do without their help.”

“Are you here with your family?”

“Yes, I came here with my husband and a 10 year- old son. But my parents decided to stay behind the line. The line — it’s how they call it — an unofficial border in an unofficial state. As soon as you cross it, you can’t be sure of anything. This war is not like a real war. There are no planes, bombs or thousands of troops. But it does look different. But, it is a war.

There are many people wearing camouflage, many military vehicles, too many windowless buildings.”

And what does your husband do?

“Oh, actually he is a mechanic. He is looking for a job now.”

She pauses and smiles sadly. And I know why.

It is nearly impossible for a person who comes from behind “the line” to get a job. People are too suspicious of them. People are afraid of employing or just dealing with people from Donbass, people who came from behind “the line.” Many of our locals consider them traitors and blame them for welcoming the war to the country. And I know that it is true for some but not all. There are still a lot of wonderful people who became prisoners of the situation. I ask Olia.

“What exactly made you leave your home?

“Fear. I couldn’t stand that feeling any more. I was afraid of going outside, of letting my child go to school. Sometimes we spent the night in the bathroom as it was the safest place. It was the only place which could save us from the others. But we left not because we felt fear, because we began to feel the lack of it.

One moment I realized that we were getting used to all of that, staying low and quiet. We became shadows. I do not want my child to live like that. It is hard for us here, but I enjoy lots of things that I never appreciated before. Oh, it’s not a hair dryer, or the microwave or the stove,” she adds quickly, laughing. “No, it’s about the long walks, relaxed people, quiet mornings.”

Olia is smiling and looks almost happy. I decide that this a good end for our conversation. I wish her good luck and promise to come again.