起死回生 – “Wake from death and return to life.”

A 74 year old Japanese man spends his life making Sense of the Senseless world he inhabited as a child during WWII. He researches, talks with family, with his older cousins and builds a narrative for himself, a Japanese American narrative, a minority perspective, different than the dominant culture’s story and much needed for all.

On February 19, 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the deportation and incarceration of Japanese Americans (62% were citizens) with Executive Order 9066 impacting nearly 120,000 people. The majority of mainland Japanese Americans were forcibly taken and relocated from their West Coast homes during the spring of 1942.

Carl Watanabe 74 years old was born in Chino, California and was an infant of a year old when he, his mother, father and four year old sister along with approximately 120,000 others were interned.

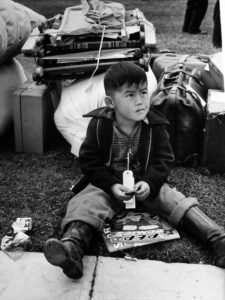

The family had been gathered up by the police or sheriff or members of the National Guard — as an infant, Carl obviously has no memory of this but was later told stories by relatives or learned through his studies: his family was forced out of their home.

You can take what you can carry, his family and the neighbors were told — and Carl’s 23 year old mother carried him and some diapers. His father held the hand of Carl’s four year old sister and managed to bring a bassinette and some treasured family keepsakes which actually held no monetary value.

Fear. Confusion. Anger. Humiliation. Embarrassment.

Shame.

Everything they could not carry was laid out in the front yard and sold off. They were ushered away watching as white people poked through the family’s keep sakes, their clothes, toys, dishes, glasses, rugs, all those things, intimate and public that it takes to create a life – out on the front lawn. People poked for something they could use or liked. Carl’s father and mother could do nothing – there was not even time to find a home for their pets.

The barracks weren’t yet built so where would they put these people in the mean time? Assembly camps. That’s where. That’s what they were called. Assembly camps. The government used racetracks, the horse stalls, temporary residences for these Japanese American Citizens.

Carl and his family were held at Santa Anita Race track where they lived in an 8 by 12 stall, white washed for the occasion of being occupied by people, instead of just one horse. The walls in the stall they occupied was 7 or 8 feet tall and sound traveled freely through the gaps between the stall and the ceiling – the sounds of family’s whispered desperation carried throughout the stable. The end of privacy really for the duration of the war. They were there for three weeks.

Some people, horrified by what was happening to their Japanese neighbors took over their farms and held them until the end of the war… most however were taken over and never returned and the reparations when they came, too little too late was minor. Remember, says Carl, these were American citizens.

After three months in the horse stall at Santa Anita, his family along with thousands of others carrying what they could were lined up, examined and loaded into the train headed for Gila, Arizona. The train windows were covered as it went through towns so nobody in the outside world would see the awkwardness of this event which needed to be hidden from the non-Japanese American citizens.

There were two camps in the dessert — Butte camp and the Canal camp — both of which were created out Pima Indian land. The Pima protested but to no avail. Carl and his family lived in the dessert photo op camp where people like Eleanor Roosevelt come to inspect the happy Japanese families held in a place with no barbed wire, no armed guards, the gun tower was not allowed to be photographed to make it seem like a family’s summer retreat to those looking into life in camp. Everyone had a number: Carl was number 14901 and his father was 14923.

Desert: Carl’s cousin tells him about Do Not Get Caught outside in one of the relentless and the all too often dust storms, unless you have a mask, or goggles, something to protect your eyes and nose, even a handkerchief would do in a pinch but definitely not recommended.

The heat was unbearable – summer temperatures ran between 104 degrees and up to 125 degrees.

In the camp where Carl’s older cousin lived there was a pit near one of the barracks. It was large and dark, dug for whatever reason who knows but it held kids in a temperature of around 90 degrees, a real break from the heat. The pit filled with kids quickly on unbearably hot days.

The barracks were tar papered without plumbing or cooking facilities along the design of military barracks built for soldiers not families. There were one or two windows for each space – the walls between “apartments “did not go all the way up – again a whispered privacy.

Whispers are the shared modulation of voice among the displaced, refugee and incarcerated groups around the world.

Reclamation of voice is literal as well as historical. To learn again, to talk — loudly, to speak, to cheer, to complain, to greet and to hold forth in a voice that isn’t a whisper, often has to be relearned and evokes fear in the process of learning. What can often remain is an anxiety about speaking up, telling your own truth. And do not stand out. It was dangerous once and the body still remembers.

It is difficult for a child, any child, trying to understand history to comprehend the reasons for the incarceration in the first place – it seemed random with Hawaii much closer to Japan and when 40 percent of Hawaiian people were Japanese or of Japanese descent – amounting to about 158,000 people and yet only a few were incarcerated — 1,500. In Hawaii, the spirit of aloha – acceptance and invitation — prevailed, and white supremacy never gained legal recognition or organization.

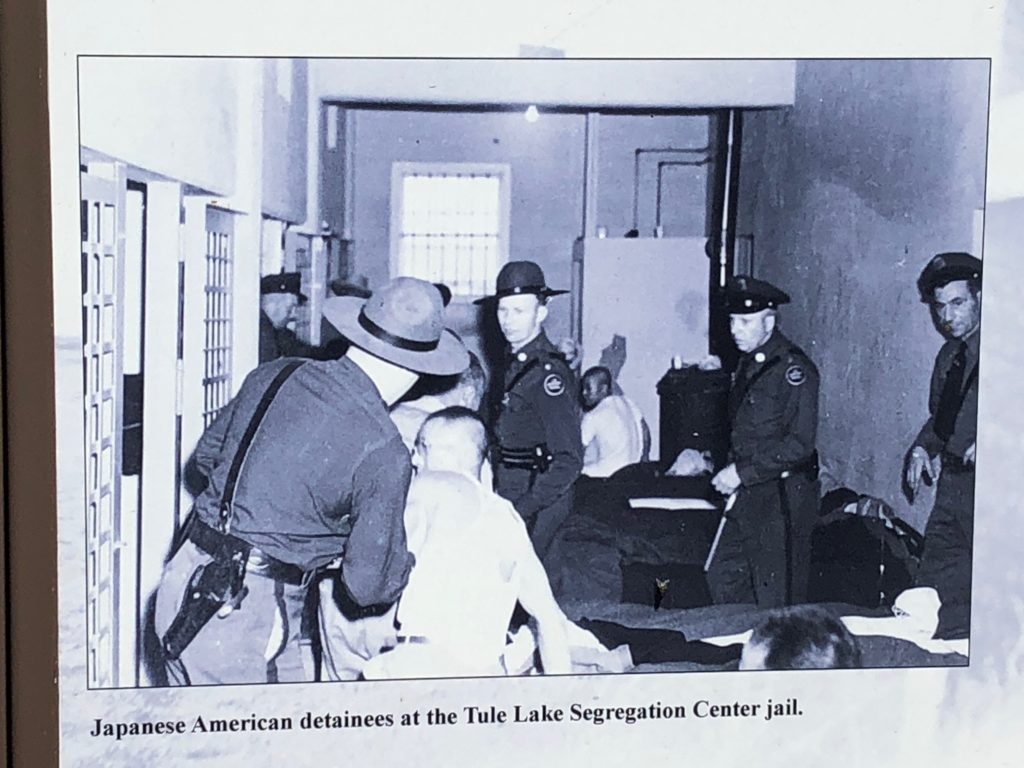

It was quite different in west coast. Racism against Japanese citizens was institutionalized and organized with groups lobbying against the normal rights granted white Americans, much as we see today toward the Mexican and Central American people in the US who are held in camps that look a great deal like camps used in the incarceration of the Japanese during WWII and in fact some are the old camps left from that period where Japanese were held. Chrystal City, Texas, being one of them.

There were some Italian and German citizens incarcerated some with the Japanese but very few in terms of the percentages compared to the Japanese.

It seems to come down to two major things:

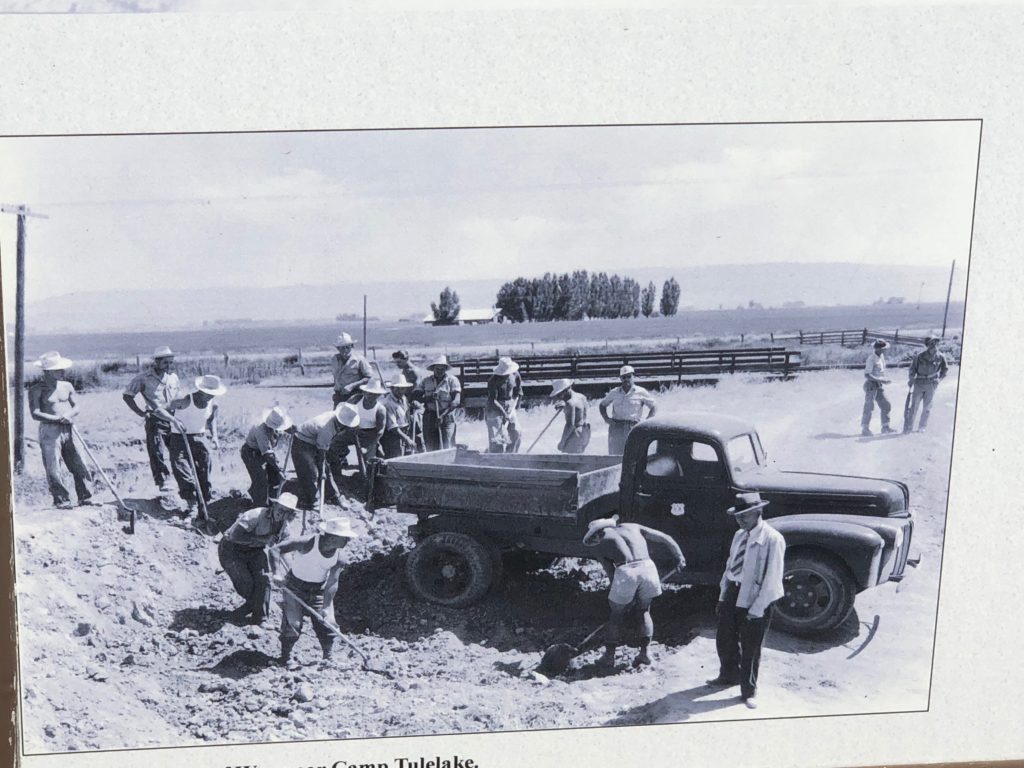

Greed/jealousy – the white population had an opportunity to pick the literal fruits of the labor of the Japanese – farms were taken, crops were harvested, money went into pockets that were not Japanese. Fishing boats were taken from moorings all along the west coast. Through the eyes of our Japanese families, we see the social and cultural context of racism and greed in which Japanese people lived during WWII. And. After!

A tiny number of the farms were held by neighbors and returned but the boats, never. There were eventual small reparations to some families.

The second and probably the bigger reason was racism. The early arrival of Japanese in the mid 1800’s looking for work to better their lives – so many of our families came to the US looking for the same thing. The arrival of the Japanese awakened a new version of racism and like other Asians; they could not own land, could not vote or run for public office. And yet they stayed. Their circumstances in terms of earning for the family were better in the US.

The younger children liked the camp. The mess hall meals were served at tables divided according to age. The noise. The clatter of plates. Probably great fun for the younger kids but Carl says, it destroyed the Japanese tradition of meal time – quiet in the family unit. The teenager’s had another story. Their lives were gone once they were taken from their homes and in the place of them there were barracks, schools set up with damaged texts and huge numbers of students per classroom. There were sports and both men and women played. Some of the teams – baseball – played in towns outside camp.

On December 26, 1943 Carl’s 23 year old mother dies – an inappropriately applied anesthetic seemed to be the cause. She stopped breathing — and a year later his five year old sister dies of a tonsillectomy. That left Carl, a two year old child and his father who must have been beyond grief and depression. Carl wonders what his life would have been like if he had had a mother and a sister. He watches intact families for cues.

Carl’s father, had nothing left in his world but his young son. When it was over he rarely talked about camp experiences.

Japanese people today wrestle over the word that would precisely describe what happened to them in 1942. The word that comes closest and even so is not quite right is incarceration, wrongful incarceration. Families. Carl tells me this.

Some people were allowed to leave the camp to work if the work was in the middle of the country but not on the coasts. His father had gotten a job in the countryside in Illinois. And they left the barracks, the dust, the lack of privacy, the barracks, the two of them.

First stop for Carl was a walkup apartment in Chicago where he age 2 ½ who remained alone after his father left for work. He was barely supervised by a woman living on the floor below. He entertained himself throwing things out the window (what things?) – Someone, whoever it was, expressed concern that Carl would eventually and accidently throw himself out the window.

Foster care: This is where he learned that not all people were kind. The foster parents, probably in need of the money, were as unkind to their own child as they were to Carl. Both boys had bathroom problems. Carl wet his bed as one would expect of a child with his life story and the real family boy was constipated. His parents sat their child on a toilet and squeezed his stomach until he yelled in pain. Why would people torture their own child? Carl’s wonderment.

But, it was here that Carl fell in love for the first time. A woman connected somehow to the foster family though quite a bit younger and kinder came to the apartment — Carl had wet his bed. The woman was very good to him, telling him in a sweet voice that he was not a bad boy. She helped change him, the bed and spent some time with him, just him. He has never forgotten her and loves her still, to this day wherever she is or isn’t any longer.

When the war was over Carl and his father went back to Chino. His father worked for a Japanese family who had figured out how to own their farm.

A new chapter: overt racism. Some things were better after the war but not all. White people were still steeped in the war culture and the war-time and pre-war racism. This made it very difficult for the Japanese people to reenter society, including Carl, a five year old boy.

In 1946 Carl attended kindergarten and was taunted, teased and pulled at, constantly threatened with beatings by his peers or the older children. He was scared. A lot. This went on all through grade school and into Junior high but then when people began forgetting the war, the intensity let up. By then Carl was nearly invisible.

He was able to keep some of the family things which would be very important to him and others with the same experiences.

Then in 19– Carl’s house caught fire. Everything went up in flames. Everything. All the family mementos that were left – photos special documents, letters — were in the fire. He lost his family… again.

Carl reads, Victor Frankel’s….Man’s Search for Meaning which was published in 1946. Victor Frankel was a holocaust survivor and a psychiatrist who was held in three different concentration camps during WWII, ending up in Auschwitz. He found that those who had a reason to survive, something meaningful, something to go back to, to live for, some responsibility, something, outlived those who surrendered to the hopelessness of having no meaning, no future.

We had to learn ourselves and, furthermore, we had to teach the despairing men, that it did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us. We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life, and instead think of ourselves as those who were being questioned by life—daily and hourly. Our question must consist, not in talk and meditation, but in right action and in right conduct. Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual. Viktor Frankel

Carl sensed that his father knew it was very important to survive – that down the road you could be helpful, down the road you could tell the real story and down the road, your son would be mature enough to hear it and in fact, needed to hear it, to know it, to know he, Carl, ad done nothing to deserve this. But finding the real and right road was another thing.

After the war and their release, Japanese people rarely spoke about experiences during WWII or told their stories until they were quite old and because many of those incarcerated were dying, those who remained would talk for archival purposes, for the people in general, providing the other necessary narrative and specifically the Japanese narrative for the younger generations. Then they spoke in quiet worn voices, the stories came pouring out.

What drew Carl to read and reread Frankel’s book: Man’s Search for Meaning. How did it help him? What were his conclusions or is he still reading the book?

Carl answers these questions. “. .. very few of us know what hunger is really like…

The Various Stages of Hunger.

1. hunger is thought of not being sated, satisfied, stuffed, not focused on food, full. We think of it as, I am no longer totally full… This stage starts as your body’s nutritional needs transition from specific nutrients to just needing calories, immediate energy.

2. …not totally full, faster on my feet but know there is something empty in me.

3) Moderately hungry: Your stomach may be growling and demanding and you want to put an end to that nagging feeling.

4) False hunger: Though this stage may look like hunger, it is connected with other biological and psychological questions that some people answer by eating. Everything. There are many other conditions that can make you feel hungry — problems like sadness, stomach ulcers, worry, loneliness, and acid stomach.

5) Satisfied: This is the stage when you are satisfied, neither hungry nor full. You are relaxed and feel comfortable. No more nagging sensation in your stomach that felt a lot like anxiety.

6) Full: You may be tempted to eat more than your need. You feel fullness in your belly making it bloated and your food may not be as tasty as it was when you began to eat.

Carl’s father, as a cook, emerged from the concentration camp with a pancake recipe created to feed 500 people.

In 1980 with pressure from the Japanese American Citizens League, Jimmy Carter opened an investigation to determine whether there was reason to intern the Japanese Americans as a threat to the safety of the US. It was determined that there was absolutely no viable military reason.

As I spent time with Carl Watanabe and he talked about his experience, he brought up the concept of Shame. Most people who have been tortured, been on the victim end of violence, often feel shame. So, when Carl Watanabe and I talked about his experience as the inheritor of the internment experience – he was a year old infant when it started – on the phenomenon of feeling shame. Wait, I said, this holds true across cultures. Carl asked me to be a bit nuanced in my talking about shame. I asked Carl for help and we exchanged emails on the subject. These are excerpts:

Shame: The whole Japanese American community (1st generation immigrants from Japan [Issei] who were still citizens of Japan, U.S. born American citizens [Nisei], and the children of Nisei, [Sansei] such as me) was ashamed that the country, from which we emanated and were emotionally connected to, had attacked the country in which we now lived and loved. People like my father understood why the vast majority of America reacted the way they did to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Any attempts to view the event from a rational point of view (e.g., that we personally had no connection to the fighting; and that we were American citizens (ironically all treated as aliens), imbued with constitutionally defined inalienable rights; and that Italian Americans and German Americans were, for the most part, spared the racism, anger and hatred), were doomed to failure. Thus, the adults felt helpless in protesting how we were being treated. We were ashamed that this happened, and even though we were not at fault, we had to shoulder the blame. That was inevitable.

There is also shame connected to being locked up and incarcerated even though you know you’re innocent. Similarly, the shame of being evicted from your home, having to sell your belongings at bargain prices, at having your belongings being displayed on the street, etc. The shame and helplessness connected with not being able to protect the lives of your pets and other animals.

Shikata ga nai: it cannot be helped.

Ultimately, for my father and his generation, the shame was also connected with having allowed this (the incarceration) to happen.

I wrote Carl again and asked if I could publish this.

Andrea, I’d forgotten that I’d written this. I’d been carrying these thoughts around for most of my life. The impact of being part of a group that had attacked our country had been pushed down within me and kept under the surface. Otherwise, I’d have become too bitter and self-absorbed with collective guilt that I’d be impossible to live with. It’s as if I had a box of forbidden memorabilia kept in an attic hideaway, rarely looked at, but always retained as I moved from house to house.

ld hold back and “stuff” down those hard feelings—sadness, anger, fear, guilt, shame. I would not share them but kept my hurts to myself. I was not encouraged to talk about my feelings nor did anyone teach me how to safely express them. This led to severe migraines and a lot of emotional shutting down. What I learned as I grew older and eventually went into the field of Social Work is that we train ourselves to hold in those painful feelings mostly through breath control – we hold our breath in order to not feel. For example, when sad, I felt I had to be “strong” and not allow myself to cry often tightening my chest and clenching my stomach to hold back tears. As I later discovered, this is done mostly through the restricting of my breath. As I learned how to consciously use my breath to rid my body of the stuck energy (which is all that emotions are anyway—energy), I found myself feeling lighter.

ld hold back and “stuff” down those hard feelings—sadness, anger, fear, guilt, shame. I would not share them but kept my hurts to myself. I was not encouraged to talk about my feelings nor did anyone teach me how to safely express them. This led to severe migraines and a lot of emotional shutting down. What I learned as I grew older and eventually went into the field of Social Work is that we train ourselves to hold in those painful feelings mostly through breath control – we hold our breath in order to not feel. For example, when sad, I felt I had to be “strong” and not allow myself to cry often tightening my chest and clenching my stomach to hold back tears. As I later discovered, this is done mostly through the restricting of my breath. As I learned how to consciously use my breath to rid my body of the stuck energy (which is all that emotions are anyway—energy), I found myself feeling lighter.