Our names carved on the lunar landscape-Revisiting Home

March 2016:

My ultramodern taxi, equipped with wifi and all other modern amenities, stops and the driver calmly tells me that this is the closest to the border that he can take me. I need to walk the rest of the distance to the checkpoint. He says he’s really sorry about that…

I take some deep breaths and encouraging myself I grab the handle of the suitcase and push, hoping the wheels hold up. They do.

“This will be over soon. I can do it, I can.”

I struggle with the heavy suitcases, heavy because I packed a lot having no idea how long I’ll need to stay in Gaza since my mother is seriously ill and it is unpredictable how long it will take for the permit to be issued.

Every time I mention the issue of the permit to friends they wonder why I need a permit to go home. I explain that I also need one to leave Gaza … they look a little perplexed. I share their confusion and try to find explanations about why this happens… How can I explain that it is the consequence of a failed peace process which led to despair and closing off of borders and separating Gaza from the West Bank and placing strict borders between them and Israel…. The peace process which started in 1993, entailed dividing the ‘Occupied Territories’ which include the West Bank and Gaza Strip to 3 parts, Area A which was to be controlled by Palestinians, Area B which had mixed control between Palestinians and Israelis. And Area C which is to be controlled by Israelis. Gaza was declared Area A, so there are no Israelis inside the Strip but Israelis control the land borders and have full control of the sea and the sky…

Thus there is a curfew on Gaza, and entering it needs to be before 19:00. If you arrive later, you would be under the mercy of the border manager if he or she will allow you in. The options are either to stay over the night at the checkpoint or go back where you came from. I was told that they usually do not allow people to wait at the Gate. The Gate by the way is all surrounded with barbed wires and the building is a modern building with cameras all over…So after dealing with legal complexities with the border guard we are able to enter Gaza.

While we wait, I remember in the late 1970s and early 1980s, travels from our home in Gaza to Jerusalem without anybody stopping us. At the time, Israeli forces controlled the whole area called the West Bank and Gaza Strip and there was no need for borders to separate the Gaza Strip or the West Bank from Israel.

Those days feel so distant like a 1940’s black and white movie or from another life I have had. Sometimes, I feel as though I am different people going through all these changes: when I travel in Europe, nobody almost stops me or even looks at my passport but when I cross the borders to this area (Palestine/Israel) my self-concept changes. I feel as if I am accused before being judged. I am guilty of some horrible act (which I am not sure what it is) and I need to prove my innocence all the time. I do feel like I am just an entity with no face, past or character and that I need to go through the motions of what I am asked to provide to show that I do not cross the line of obedience.

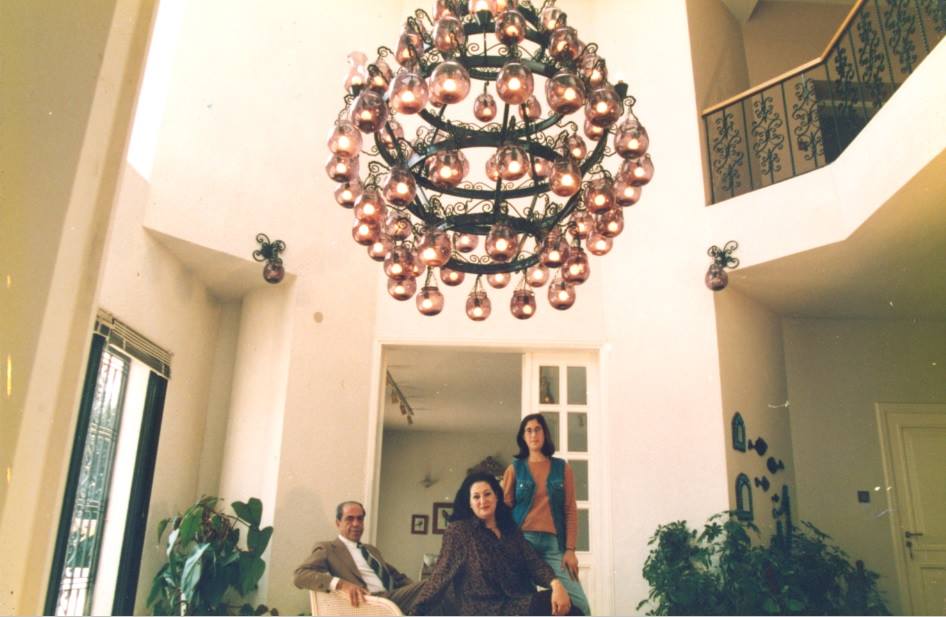

On the way to my current home, we pass by what remained of our old house which was bombed in the recent war on Gaza. By the way, that was the third time our house was bombed by Israeli forces. One of the reasons for its continuous targeting is its location. It is located near the Eastern border separating the Gaza Strip from Israel. It is a farmland and in the past we had animals like horses, goats, cows and chicken living there. This house was the dream house of my parents since they returned to Gaza from Kuwait where my father was offered employment in the 1960s. Since returning to Gaza, things were quite tough on the work front and my father tried several projects among which was agriculture which he and my mother established on this farmland. So they were waiting for the opportunity to have some savings to start building the house. They eventually did start it in the 1980s but it took them 10 years to finish it (having four daughters and living in the Gaza Strip does not provide the best opportunities to build a new house).

The house was also a dream house because it was built on the land that my father inherited from his father. It was surrounded by some residential areas and orange orchards which is what Gaza was known for. It was close to the Eastern borders with Israel and the borders have usually farmland for security reasons. So standing at the second floor of our house our eyes only saw green farm land which was such a contrast to the Western side of the house, which overlooked Gaza, one of the most populated areas in the world

These memories had no relation with what I am witnessing throughout my ride, memories of my wedding, of celebrating my mother’s election for the parliament, my father’s mayor ship, his illness, all of these memories are only kept in our souls. They do not belong to any physical entity. What I saw, was rubble, where the iron blades of the house’s foundation as if they decided to change their direction and dive back into the ground. Small pieces of window glass, pieces of door-wood, a torn photo, a dead flower were all what I saw. In my mind carved is my mother’s photo sitting on the rubble and her eyes dazing off the horizon. What was she thinking? All is gone? Where to start now? Where are our memories? I wonder….

But then I remember times when we had fun and more joyful memories float in my mind. I remember as a child playing under and climbing up the Sycamore tree, with its far reaching branches full of green year long (this tree survives with little water and was considered scared by the Ancient Egyptians). That was before building the house, however there was another building which consisted of two rooms and they were what we called my grandfather’s office because he used it to keep track of the farm’s matters and expenses. The office had his desk and his copybooks. My father used this office when we came back from Kuwait. He would sit in that office and discuss farm matters with the farm keeper. The family of the farm keeper had been living there for decades. They even had their eldest boy called Aown, my father’s name, to show how close they were to us. They were from a village close to the town of Al Magdal or Askalan (now it is called Ashqelon because it was taken by Israel in 1948 and is now inside Israel). My grandfather offered them protection when they fled their town and they were grateful to him and his family ever after.

Through the same road, I also remember sitting in my mother’s car, the silver Renault with its greyish velvety seats… warmly squeezed in the back with my three sisters, my youngest sister was still very small so we could fit in…sometimes even sliding lower in the car to enjoy our retreat. We (the four sisters) would be in the back seat with our nanny in the front who would also lean back and talk to us so as not to feel the rigid separation of the front and back seats of the car, a thing which I always wondered why designers could not find a more sociable design to facilitate mingling in the car …

The windows were open and we could smell the orange orchards and the sea breeze…. I can almost hear us laughing and singing. …we would give ourselves to the song to forget all our surroundings … ‘On the lunar landscape I will write our names’ a verse which I cannot forget because it was one of my mother’s and our favorite songs. It was sung by a Syrian singer who became famous after moving to Egypt (where all the great composers lived back then), Faiyza Ahmad. Another verse which always reminds me of those rides and whenever I hear it I relive those moments is, ‘my beautiful homeland’, by the Egyptian-Italian-French singer Dalida…Only our mother knew our destination so we completely left it up to her to get us home…

In current time, things have been completely altered, my mother is bedridden, our old house is gone, more complex checking procedures are set, and still, my childhood memories are very alive and go with me ….where can I mark the border between, past vs present, life vs. death, joy vs. sadness, war vs. resistance, construction vs. deconstruction, inside vs. outside, safety vs. threat the list of comparisons goes on… my identity vs. others, my memories vs. current moment… a continuous process of negotiation and renegotiation of myself and borders around me, growing heavier, deeper, layer after layer like memories are thick with sadness, confusion and never knowing the outcome, never fully trusting enough to feel normal, always on edge …. Where will take this trip take me?

Salma A. Shawa

Walking towards the sea, I ran into the volunteer on duty. She was a psychologist who worked with refugees in France. The grassroots solidarity movement in support of asylum-seekers and migrants in Greece was hearteningly international in nature. “The boat is coming here, and no one is answering their phones at the apartment,” she said. They hadn’t announced the final destination on the radio. I returned to the one bedroom apartment that housed six of us, announced the arrival of the boat, and then made my way to the small port. I could see two lifeguard boats accompanying the boat ashore. As they entered the port, lifeguards shouted instructions in Arabic to the man steering the boat who was clearly new to his role. A loud cheer erupted from the boat when it became clear to everyone onboard they had actually made it.

Walking towards the sea, I ran into the volunteer on duty. She was a psychologist who worked with refugees in France. The grassroots solidarity movement in support of asylum-seekers and migrants in Greece was hearteningly international in nature. “The boat is coming here, and no one is answering their phones at the apartment,” she said. They hadn’t announced the final destination on the radio. I returned to the one bedroom apartment that housed six of us, announced the arrival of the boat, and then made my way to the small port. I could see two lifeguard boats accompanying the boat ashore. As they entered the port, lifeguards shouted instructions in Arabic to the man steering the boat who was clearly new to his role. A loud cheer erupted from the boat when it became clear to everyone onboard they had actually made it.