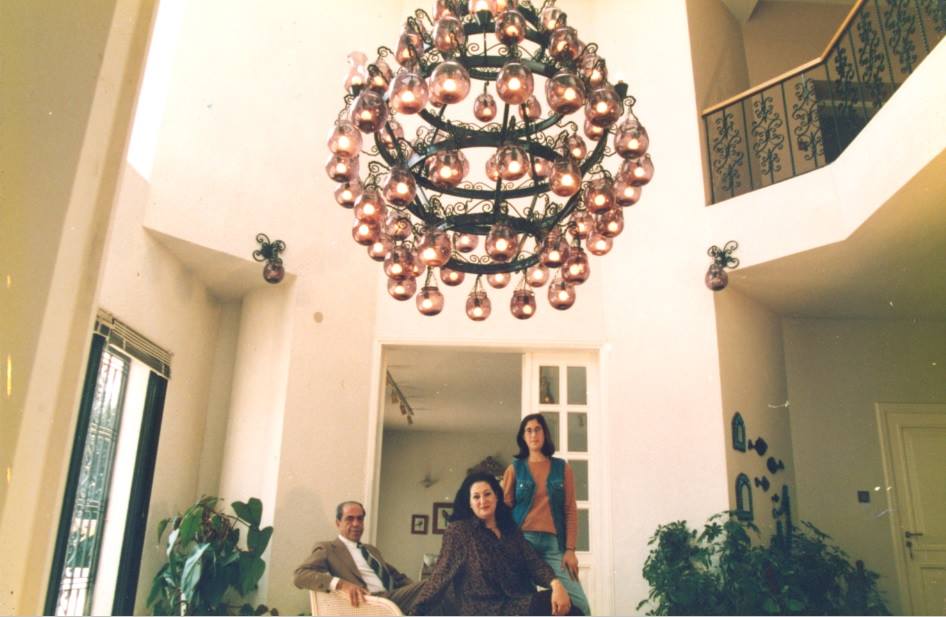

Hello, Andrea here. I asked Patti Gora Mcraven to write this when the abstraction of war toxins and its impact on health was brought home in my knowing and loving people who were impacted by this: especially a beautiful little Kosovar girl, Klara, whose health has been fragile. Why?

We believe, with good reason, that the toxins of war that have poisoned soil in which food is grown is the ground out of which ill health for children grows.

We believe, with good reason, that the toxins of war that have poisoned soil in which food is grown is the ground out of which ill health for children grows.

Patti is an environmentalist, Activist and Inspiration to all of us to not just KNOW of these conditions but DO something. She told me that this piece was particularly difficult for her to write. She knows a great deal about the toxins of war but for this piece she dove even deeper into the research which she said is even worse than she imagined.

Those of us who find this information difficult to deal with, will find strength as they find their voices matter and they can raise them — the Women’s March has given us this. The people impacted by these toxic soils are real people that you, the reader will meet on the pages of this website. And you will see that in so many countries around the world, war isn’t over when its over, it continues in the bodies of the children as they begin showing signs of ill health clearly related to the toxins of war.

Below is Patti’s piece. I am so grateful she is willing to stay with it as it gets difficult for her. How little do I think of the responses our courageous reporters of painful events or conditions who are impacted by what they learn, see and know.

*********

Once upon a time, I was a forestry major. I didn’t last long once I realized that this course of study meant I’d be hired to figure out board feet and cut down the trees I loved so deeply. I didn’t want to do that, so I had to switch to something based on natural resources, something less mercenary and more focused on the web of relationships so crucial to this beautiful planet.

After a few years of wandering I became a mother myself. My beloved trees still “schooled” me; I remember being very pregnant and encountering my apple tree, heavy with fruit, much like me. I had a moment of understanding how that particular tree felt in a way I never had before. The difference was motherhood, and being responsible for another life inside of me. My apple tree and I understood each other.

I would return to use my knowledge of ecology and natural resources as my son was born with some pretty serious issues. He had severe asthma and allergies to many foods. He gasped for air a lot. It was frightening. Of course, as any mother would, I began to search for answers and for help.

I learned that the local practice of burning large fields after harvest were the source of the repeated bouts of pneumonia and sinus infections and asthma that my son had. I naturally did my best to bring science and understanding to the situation, examining why the practice of burning existed and why it was so pervasive. The short story is that my husband and I along with other parents of disabled kids ended up challenging the way our state conducted such burns. We actually made a federal case out of it. That phrase is used a lot to suggest wild exaggeration on the part of one party, but when a healthy 21 year old in my town died from this horrible air pollution, we knew we had to act. So we sued on behalf of our sick children and after a long and protracted battle, we won and changed the way burns were conducted so that more people wouldn’t die. You would think that would be easy, but it wasn’t. It cost us all our free time, our money, and pretty much our sanity. And at least 3 good people who worked with us died of unusual cancers, including my own husband. So this is not something I joke about.

As I studied what was in the smoke (things like particulate matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and toxics) I began to notice something disturbing. There were thousands of mothers and fathers just like us who were fighting similar battles all over this country, and indeed, all over the world. Each one of us had to do singular battle with billion dollar industries who were invested in having it their way.

There was the problem of coal-ash spilling and poisoning communities and fecal contamination from CAFO’s which are large animal farms (see And the Waters Turned to Blood by Rodney Barker); toxic waste used as “fertilizer” to be used on crops even as those crops uptake the arsenic and cadmium contained in that “fertilizer” (see Fateful Harvest: The True Story of a Small Town, a Global Industry, and a Toxic Secret by Duff Wilson); the fracking problem of contaminated water and toxic emissions; just to name a few here in this country. We haven’t even covered Superfund sites like Love Canal or the Silver Valley in Idaho or the lead poisoning in the water in Flint and other communities, or the poisoning of entire communities like Libby, Montana by the WR Grace corporation from asbestos.

With the recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, I learned that 18 countries use DU manufactured bombs made with depleted uranium. This is uranium that has been used in the nuclear enrichment process, but has been “recycled” to make armor-piercing bombs. The problem is that these bombs aerosolize the uranium and contaminate the soil and the air around impact. There have been several compelling papers written to attempt to document the harm being done to populations that remain after the bombing. Rising levels of thyroid cancer have been documented in Serbia, as well as increased in other cancers.

The changing nature of war means that no longer are refugees able to return home safely; we are now creating an entirely new and deadly situation by poisoning the environment in places where war is waged. The article I was researching for this piece in Scientific American, also has a buffet of tragedies to choose from: Agent Orange contamination is more extensive than first thought and chemical weapons in Syria, bioterror (yes, that’s a word now) and we don’t even know what’s going on in the secret programs that are most assuredly being developed. (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/afghanistan-karzai-us-depleted-uranium/)

Although there are principles of conflict which state that those who use such weapons are responsible for clean up and for avoiding war crimes, we can see that clean up rarely happens and that local populations bear the cost when they have already been traumatized by war and dislocation.

It seems to me that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. We must learn that these fairly recent mechanisms of war are only harming the earth and all its inhabitants and creating massive displacements of refugees who can no longer safely return home. According to the United Nations, the number of refugees in the world has reached the highest number ever recorded.

“After an increase of five million last year, the number of people displaced by conflict – refugees, asylum seekers or those displaced internally – was at an estimated 65.3 million by the end of 2015.

It is the equivalent of one in every 113 people on the planet, according to the UN Refugee Agency, and if considered a nation would make up the 21st largest in the world.” (http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/refugee-crisis-migrants-world-day-un-a7090986.html)

There is no home to return to if the water is poisoned, the earth can’t grow food safe to eat and the very air can be radioactive or filled with toxic pollution.

Absent from the discussions of what to do about refugee populations is remediation of the land, water and air in war-torn countries as well as rebuilding the infrastructure.

I wish I had some decent answers. I wish I could bring a solution to this issue of new warfare poisoning the very earth we depend upon for sustenance, much like my beloved apple tree gave me fruit each year. Perhaps we need a new set of rules for war which include the cost of remediation of soil, water and air upon the end of any given campaign.

We simply must re-think conflict. It is no longer possible to poison, with impunity, the very ground being fought upon. We are all interconnected.

It seems to me that there are several core fallacies at the heart of our current paradigm:

- Everything has a price

- Anything that has a price can be extracted, traded or sold

- We are entranced by some sort of competition to see who gets the “most” because we have a false notion that having the “most” guarantees our safety somehow.

As I’ve watched repeated fights attempting to hold polluters accountable, I’ve learned that they wield immense power in the current paradigm. That is to say, they have accumulated enormous stores of money, power and influence to game the system.

Environmental activists have been able to hold some of these groups accountable by publicly shaming them and highlighting the lack of basic human decency in their polluting ways.

But we seem to be numbing out. After all, how many outrages can spur us to action anymore? We are weary of bad news and need soothing. We are all traumatized by the state of affairs of the planet’s health and vitality. There are indeed things that money can’t buy. This includes the longing for human connection and meaning, as well as beauty. I am buoyed by the movements to buy less, live smaller and share more. I believe there is a change of spirit and heart coming to be born. I think that human connection, compassion and interaction are the antidotes to the dark forces that have played us like chess pieces. I don’t have all the answers as to how, but I do know that a small number of dedicated folks getting together for common cause can create miracles.

Depleted uranium effects:

In Serbia: “Depleted Uranium used by NATO during bombing of Serbia takes its toll” by InSerbia with agencies, March 29, 2016

Accessed on 1-16-17 at:

https://inserbia.info/today/2016/03/depleted-uranium-used-by-nato-during-bombing-of-serbia-takes-its-toll/

BELGRADE – The use of depleted uranium during NATO bombing of Serbia has caused long-term damage to Serbia and the Serbian people. Because every year we have an increase in the number of cancer cases by 25 percent over the previous year. Figures in the case of patients in Kosovska Mitrovica support this fact, as in 2011 here were registered 185 of them, the following year, 225 and in 2013 – 250. Therefore, the gloomy forecasts, imposed back in 2002, that the use of depleted uranium during the aggression of Western military alliance against FRY will cause an epidemic of malignant diseases, turned out to be accurate, said dr. Nebojsa Srbljak for Serbian daily “Vecernje Novosti”.

Dr Srbljak, a cardiologist at the ZTC in Kosovska Mitrovica and founder of the NGO “Angel of Mercy” which deals with data on the number of patients with malignancy in Kosovo, explained for the daily that “those who used the depleted uranium had to know what consequences it causes”. He said that the study of his organization, which cover the period of two years before and two years after the bombing, clearly shows that the number of patients with malignant diseases is caused by radioactivity, and not stress and other bad life habits.

“Let us remember the example of Italy which has revealed that their soldiers, who stayed in Kosovo, were irradiated and that the increased number of hematological diseases is a direct consequence of the use of depleted uranium ammunition,” said dr. Srbljak. “Italian KFOR soldiers were deployed where the most of the ammunition with depleted uranium was used, in Pec, Djakovica, in Kosare. Their families, as far as I know, have received compensation.”

Dr. Srbljak urges the authorities that our country formally request compensation, not only for material damage but also because of the increase in the number of patients with malignant diseases. The cardiologist claims that someone was trying to minimize the information he and his team published back in 2002 that the number of patients with malignant diseases was increased by almost 200 percent compared to the period before the bombing.

“It became clear that we are right when our neighbors Albanians started to go to Belgrade for a treatment. Because, and that is obvious, they have confidence in the expertise of Serbian doctors. I therefore think that our proposal, to open a branch of Oncology Institute in Belgrade here in (Kosovska) Mitrovica could finally be realized.”

- Abstract viewed on 1-16-17 at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24778342

Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2014 Jun;65(2):189-97. doi: 10.2478/10004-1254-65-2014-2427.

Environmental radioactivity in southern Serbia at locations where depleted uranium was used.

Sarap NB, Janković MM, Todorović DJ, Nikolić JD, Kovačević MS.

Abstract

In the 1999 bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, NATO forces used ammunition containing depleted uranium. The cleaning of depleted uranium that followed was performed in southern Serbia by the Vinča Institute of Nuclear Sciences between 2002 and 2007 at the locations of Pljačkovica, Borovac, Bratoselce, and Reljan. This paper presents detailed results of radioactivity monitoring four years after cleaning (2011), which included the determination of gamma emitters in soil, water, and plant samples, as well as gross alpha and beta activities in water samples. The gamma spectrometry results showed the presence of natural radionuclides 226Ra, 232Th, 40K, 235U, 238U, and the produced radionuclide 137Cs (from the Chernobyl accident). In order to evaluate the radiological hazard from soil, the radium equivalent activity, the gamma dose rate, the external hazard index, and the annual effective dose were calculated. Considering that a significant number of people inhabit the studied locations, the periodical monitoring of radionuclide content is vital.

- Accessed on 1-16-17

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12500799

J Environ Radioact. 2003;64(2-3):121-31.

Isotopic composition and origin of uranium and plutonium in selected soil samples collected in Kosovo.

Danesi PR1, Bleise A, Burkart W, Cabianca T, Campbell MJ, Makarewicz M, Moreno J, Tuniz C, Hotchkis M.

Author information

Abstract

Soil samples collected from locations in Kosovo where depleted uranium (DU) ammunition was expended during the 1999 Balkan conflict were analysed for uranium and plutonium isotopes content (234U, 235U, 236U, 238U, 238Pu, (239 + 240)Pu). The analyses were conducted using gamma spectrometry (235U, 238U), alpha spectrometry (238Pu, (239 + 240)Pu), inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (234U, 235U, 236U, 238U) and accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) (236U)). The results indicated that whenever the U concentration exceeded the normal environmental values (approximately 2 to 3 mg/kg) the increase was due to DU contamination. 236U was also present in the released DU at a constant ratio of 236U (mg/kg)/238U (mg/kg) = 2.6 x 10(-5), indicating that the DU used in the ammunition was from a batch that had been irradiated and then reprocessed. The plutonium concentration in the soil (undisturbed) was about 1 Bq/kg and, on the basis of the measured 238Pu/(239 + 240)Pu, could be entirely attributed to the fallout of the nuclear weapon tests of the 1960s (no appreciable contribution from DU).

Accessed 1-16-17

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14515407

Croat Med J. 2003 Oct;44(5):520-32.

Undiagnosed illnesses and radioactive warfare.

Duraković A1.

Author information

1Uranium Medical Research Center, 3430 Connecticut Avenue/11854, Washington, DC 20008, USA. asaf@umrc.net

Abstract

The internal contamination with depleted uranium (DU) isotopes was detected in British, Canadian, and United States Gulf War veterans as late as nine years after inhalational exposure to radioactive dust in the Persian Gulf War I. DU isotopes were also identified in a Canadian veteran’s autopsy samples of lung, liver, kidney, and bone. In soil samples from Kosovo, hundreds of particles, mostly less than 5 microm in size, were found in milligram quantities. Gulf War I in 1991 resulted in 350 metric tons of DU deposited in the environment and 3-6 million grams of DU aerosol released into the atmosphere. Its legacy, Gulf War disease, is a complex, progressive, incapacitating multiorgan system disorder. The symptoms include incapacitating fatigue, musculoskeletel and joint pains, headaches, neuropsychiatric disorders, affect changes, confusion, visual problems, changes of gait, loss of memory, lymphadenopathies, respiratory impairment, impotence, and urinary tract morphological and functional alterations. Current understanding of its etiology seems far from being adequate. After the Afghanistan Operation Anaconda (2002), our team studied the population of Jalalabad, Spin Gar, Tora Bora, and Kabul areas, and identified civilians with the symptoms similar to those of Gulf War syndrome. Twenty-four-hour urine samples from 8 symptomatic subjects were collected by the following criteria: 1) the onset of symptoms relative to the bombing raids; 2) physical presence in the area of the bombing; and 3) clinical manifestations. Control subjects were selected among the sympotom-free residents in non-targeted areas. All samples were analyzed for the concentration and ratio of four uranium isotopes, (234)U, (235)U, (236)U and (238)U, by using a multicollector, inductively coupled plasma ionization mass spectrometry. The first results from the Jalalabad province revealed urinary excretion of total uranium in all subjects significantly exceeding the values in the nonexposed population. The analysis of the isotopic ratios identified non-depleted uranium. Studies of specimens collected in 2002 revealed uranium concentrations up to 200 times higher in the districts of Tora Bora, Yaka Toot, Lal Mal, Makam Khan Farm, Arda Farm, Bibi Mahro, Poli Cherki, and the Kabul airport than in the control population. Uranium levels in the soil samples from the bombsites show values two to three times higher than worldwide concentration levels of 2 to 3 mg/kg and significantly higher concentrations in water than the World Health Organization maximum permissible levels. This growing body of evidence undoubtedly puts the problem of prevention and solution of the DU contamination high on the priority list.

Accessed 1-16-17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11259733

On depleted uranium: gulf war and Balkan syndrome.

Duraković A1.

Author information

Abstract

The complex clinical symptomatology of chronic illnesses, commonly described as Gulf War Syndrome, remains a poorly understood disease entity with diversified theories of its etiology and pathogenesis. Several causative factors have been postulated, with a particular emphasis on low level chemical warfare agents, oil fires, multiple vaccines, desert sand (Al-Eskan disease), botulism, Aspergillus flavus, Mycoplasma, aflatoxins, and others, contributing to the broad scope of clinical manifestations. Among several hundred thousand veterans deployed in the Operation Desert Storm, 15-20% have reported sick and about 25,000 died. Depleted uranium (DU), a low-level radioactive waste product of the enrichment of natural uranium with U-235 for the reactor fuel or nuclear weapons, has been considered a possible causative agent in the genesis of Gulf War Syndrome. It was used in the Gulf and Balkan wars as an armor-penetrating ammunition. In the operation Desert Storm, over 350 metric tons of DU was used, with an estimate of 3-6 million grams released in the atmosphere. Internal contamination with inhaled DU has been demonstrated by the elevated excretion of uranium isotopes in the urine of the exposed veterans 10 years after the Gulf war and causes concern because of its chemical and radiological toxicity and mutagenic and carcinogenic properties. Polarized views of different interest groups maintain an area of sustained controversy more in the environment of the public media than in the scientific community, partly for the reason of being less than sufficiently addressed by a meaningful objective interdisciplinary research.

Accessed 1-16-17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17299528

J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2008 Jan;18(1):95-108. Epub 2007 Feb 14.

Gulf war depleted uranium risks.

Marshall AC1.

Author information

1Consultant for Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87047, USA. physbang1@msn.com

Abstract

US and British forces used depleted uranium (DU) in armor-piercing rounds to disable enemy tanks during the Gulf and Balkan Wars. Uranium particulate is generated by DU shell impact and particulate entrained in air may be inhaled or ingested by troops and nearby civilian populations. As uranium is slightly radioactive and chemically toxic, a number of critics have asserted that DU exposure has resulted in a variety of adverse health effects for exposed veterans and nearby civilian populations. The study described in this paper used mathematical modeling to estimate health risks from exposure to DU during the 1991 Gulf War for both US troops and nearby Iraqi civilians. The analysis found that the risks of DU-induced leukemia or birth defects are far too small to result in an observable increase in these health effects among exposed veterans or Iraqi civilians. The analysis indicated that only a few ( approximately 5) US veterans in vehicles accidentally targeted by US tanks received significant exposure levels, resulting in about a 1.4% lifetime risk of DU radiation-induced fatal cancer (compared with about a 24% risk of a fatal cancer from all other causes). These veterans may have also experienced temporary kidney damage. Iraqi children playing for 500 h in DU-destroyed vehicles are predicted to incur a cancer risk of about 0.4%. In vitro and animal tests suggest the possibility of chemically induced health effects from DU internalization, such as immune system impairment. Further study is needed to determine the applicability of these findings for Gulf War exposure to DU. Veterans and civilians who did not occupy DU-contaminated vehicles are unlikely to have internalized quantities of DU significantly in excess of normal internalization of natural uranium from the environment.

Accessed 1-16-17 at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27895436

Hippokratia. 2016 Jan-Mar;20(1):9-23.

Rising incidence of thyroid cancer in Serbia.

Slijepcevic N1, Zivaljevic V2, Paunovic I2, Diklic A2, Zivkovic P3, Miljus D3, Grgurevic A4, Sipetic S4.

Author information

1Centre for Endocrine surgery, Clinical Centre of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia.

2Centre for Endocrine surgery, Clinical Centre of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia; School of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia.

3Institute of Public Health of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia.

4Institute of Epidemiology, School of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia; School of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In the past decade, the incidence of thyroid cancer (TC) has shown a stable increase, for both sexes, in many parts of the world at a rate faster than for any other type of malignancy. The aim of our study was to analyze and report changes in TC incidence in Serbia, as well as to evaluate potential reasons for these changes. So far, the incidence of TC in Serbia has not been reported.

MATERIAL AND METHODS:

This is a retrospective descriptive epidemiological study of TC data from the Cancer Register for Serbia for a ten year period, from 1999 to 2008. Crude rates (CR), age-specific rates (ASR), age-adjusted rates (AAR), linear trends and average annual percentage changes (AAPC) were calculated and analyzed.

RESULTS:

TC incidence increased substantially for both genders with the highest increase in 2007 for the age group 50-59 (females 14.2, males 10.3). TC was three times more common in females (CR 4.7:1.5). The AAR for females ranged 1.9-4.8 (3.3, 95% CI 2.6-4.0), for males 1.0-2.6 (1.0, 95% CI 0.8-1.2) and for both sexes combined 1.4-3.2 (2.2, 95% CI 1.7-2.6). The incidence trend for males showed an increase (y =0.05x + 0.70, p =0.058). It was highly statistically significant for females (y =0.31x + 1.61, p <0.001) and both genders combined (y =0.18x + 1.18, p <0.001). AAPC was highest for ages 20-29 and 30-39, for females (+25.2%) and males (+17.3%), respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

We found a substantial increase in TC incidence in Serbia for both genders. The highest increase in TC incidence was found in females aged 20 to 29 years while the highest incidence was found in the age group 50 to 59.

KEYWORDS:

Serbia; Thyroid cancer; age-adjusted rates; age-specific rates; average annual percentage changes; crude rates; incidence

Accessed 1-16-17

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12500797

J Environ Radioact. 2003;64(2-3):93-112.

Properties, use and health effects of depleted uranium (DU): a general overview.

Bleise A1, Danesi PR, Burkart W.

Author information

1International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Department of Nuclear Science and Applications, Wagramer Strasse 5, P.O. Box 100, A-1400 Vienna, Austria.

Abstract

Depleted uranium (DU), a waste product of uranium enrichment, has several civilian and military applications. It was used as armor-piercing ammunition in international military conflicts and was claimed to contribute to health problems, known as the Gulf War Syndrome and recently as the Balkan Syndrome. This led to renewed efforts to assess the environmental consequences and the health impact of the use of DU. The radiological and chemical properties of DU can be compared to those of natural uranium, which is ubiquitously present in soil at a typical concentration of 3 mg/kg. Natural uranium has the same chemotoxicity, but its radio-toxicity is 60% higher. Due to the low specific radioactivity and the dominance of alpha-radiation no acute risk is attributed to external exposure to DU. The major risk is DU dust, generated when DU ammunition hits hard targets. Depending on aerosol speciation, inhalation may lead to a protracted exposure of the lung and other organs. After deposition on the ground, re-suspension can take place if the DU containing particle size is sufficiently small. However, transfer to drinking water or locally produced food has little potential to lead to significant exposures to DU. Since poor solubility of uranium compounds and lack of information on speciation precludes the use of radio-ecological models for exposure assessment, bio-monitoring has to be used for assessing exposed persons. Urine, feces, hair and nails record recent exposures to DU. With the exception of crews of military vehicles having been hit by DU penetrators, no body burdens above the range of values for natural uranium have been found. Therefore, observable health effects are not expected and residual cancer risk estimates have to be based on theoretical considerations. They appear to be very minor for all post-conflict situations, i.e. a fraction of those expected from natural radiation.

Accessed 1-16-17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14664872

environ Int. 2004 Mar;30(1):123-34.

Environmental and health consequences of depleted uranium use in the 1991 Gulf War.

Bem H1, Bou-Rabee F.

Author information

1Institute of Applied Radiation, Technical University of Lodz, ul. Zwirki 36, 90-924, Lodz, Poland. henrybem@ck-sg.p.lodz.pl

Abstract

Depleted uranium (DU) is a by-product of the 235U radionuclide enrichment processes for nuclear reactors or nuclear weapons. DU in the metallic form has high density and hardness as well as pyrophoric properties, which makes it superior to the classical tungsten armour-piercing munitions. Military use of DU has been recently a subject of considerable concern, not only to radioecologists but also public opinion in terms of possible health hazards arising from its radioactivity and chemical toxicity. In this review, the results of uranium content measurements in different environmental samples performed by authors in Kuwait after Gulf War are presented with discussion concerning possible environmental and health effects for the local population. It was found that uranium concentration in the surface soil samples ranged from 0.3 to 2.5 microg g(-1) with an average value of 1.1 microg g(-1), much lower than world average value of 2.8 microg g(-1). The solid fallout samples showed similar concentrations varied from 0.3 to 1.7 microg g(-1) (average 1.47 microg g(-1)). Only the average concentration of U in solid particulate matter in surface air equal to 0.24 ng g(-1) was higher than the usually observed values of approximately 0.1 ng g(-1) but it was caused by the high dust concentration in the air in that region. Calculated on the basis of these measurements, the exposure to uranium for the Kuwait and southern Iraq population does not differ from the world average estimation. Therefore, the widely spread information in newspapers and Internet (see for example: [CADU NEWS, 2003. http://www.cadu.org.uk/news/index.htm (3-13)]) concerning dramatic health deterioration for Iraqi citizens should not be linked directly with their exposure to DU after the Gulf War.

PMID: 14664872 DOI: 10.1016/S0160-4120(03)00151-X

Campaign against depleted uranium

http://www.cadu.org.uk/intro.htm

This is the text of the most recent CADU leaflet, all details are correct as of November 2008. You can download a pdf of the leaflet in high resolution (1.6MB), and low resolution (658KB). You are very welcome to distribute this material, so long as it is not for financial gain, but please attibute it to CADU & do not make any alterations without prior persmission.

What is DU?

- Depleted Uranium is a waste product of the nuclear enrichment process.

- After natural uranium has been ‘enriched’ to concentrate the isotope U235 for use in nuclear fuel or nuclear weapons, what remains is DU.

- The process produces about 7 times more DU than enriched uranium.

Despite claims that DU is much less radioactive than natural uranium, it actually emits about 75% as much radioactivity.1 It is very dense and when it strikes armour it burns (it is ‘pyrophoric’).2 As a waste product, it is stockpiled by nuclear states, which then have an interest in finding uses for it.

DU is used as the ‘penetrator’ – a long dart at the core of the weapon – in armour piercing tank rounds and bullets. It is usually alloyed with another metal. When DU munitions strike a hard target the penetrator sheds around 20% of its mass, creating a fine dust of DU, burning at extremely high temperatures.3

This dust can spread 400 metres from the site immediately after an impact.4 It can be re-suspended by human activity, or by the wind, and has been reported to have traveled twenty-five miles on air currents.5 The heat of the DU impact and secondary fires means that much of the dust produced is ceramic, and can remain in the lungs for years if inhaled.6

Who uses it?

At least 18 countries are known to have DU in their arsenals:

- UK

- US

- France

- Russia

- China

- Greece

- Turkey

- Thailand

- Taiwan

- Israel

- Bahrain

- Egypt

- Kuwait

- Saudi Arabia

- India

- Belarus

- Pakistan

- Oman

Most of these countries were sold DU by the US, although the UK, France and Pakistan developed it independently.

Only the US and the UK are known to have fired it in warfare. It was used in the 1991 Gulf War, in the 2003 Iraq War, and also in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the 1990s and during the NATO war with Serbia in 1999. While its use has been claimed in a number of other conflicts, this has not been confirmed.7

Health Problems

- DU is both chemically toxic and radioactive. In laboratory tests it damages human cells, causing DNA mutations and other carcinogenic effects.8

- Reports of increased rates of cancer and birth defects have consistently followed DU usage.

- Representatives from both the Serbian and Iraqi governments have linked its use with health problems amongst civilians.9

- Many veterans remain convinced DU is responsible for health problems they have experienced since combat

Article by The Guardian on the ecological impacts of war

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/nov/06/whats-the-environmental-impact-of-modern-war

From that article:

During the first Gulf War, the US bombed Iraq with 340 tonnes of missiles containing depleted uranium. Mac Skelton, a contributor to the Costs of War project at Brown, is writing his doctoral thesis in anthropology on Iraqis seeking cancer care in Lebanon. One of his articles reviews a number of studies that suggest a potential increase of cancer rates in Iraq, which has been linked to the shells used by the US and UK militaries.

In all wars, displaced people congregate en masse without infrastructure to support their presence. Refugees turn to the environment in order to fulfil their basic needs.

During the Rwandan civil war almost three-quarters of a million people lived in camps on the edge of Virunga national park. According to the Worldwatch Institute around 1,000 tonnes of wood was removed from the park every day for two years in order to build shelters, feed cooking fires and created charcoal for sale. By the time the conflict ended 105 sq km of forest had been damaged and 35 sq km stripped bare.

In Afghanistan too, wildlife and habitats have disappeared. The past 30 years of war has stripped the country of its trees, including precious native pistachio woodlands. The Costs of War Project says illegal logging by US-backed warlords and wood harvesting by refugees caused more than one-third of Afghanistan’s forests to vanish between 1990 and 2007. Drought, desertification and species loss have resulted. The number of migratory birds passing through Afghanistan has fallen by 85%.

http://www.bandepleteduranium.org/en/depleted-uranium-frequently-asked-questions#10

Are DU weapons illegal under current international law?

Using DU runs counter to the basic rules and principles enshrined in written and customary International Humanitarian Law. This relates among other things to:

- The general principle on the protection of civilian populations from the effects of hostilities.

- The principle that the right of the parties to an armed conflict to choose their methods or means of warfare is not unlimited.

- The principle that the employment in armed conflicts of weapons, projectiles, and material and methods of warfare of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering is forbidden.

- The prohibition of the use of poisonous weapons according to Art. 23 para.1 of the Hague Regulations and the rules of the Poison Gas Protocol.

- The prohibition of widespread damage to the natural environment and unjustified destruction according to the Hague Regulations and the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions.

- The principle of ‘humanitarian proportionality’, which is contained in the St. Petersburg Declaration.

- Additionally both Humanitarian Law and Environmental Law are based on the principle of precaution and proportionality, which at the very least, states should adhere to. Two resolutions of the Sub-Commission to the UN Commission on Human Rights (1996/16 and 1997/36) state that the use of uranium ammunition is not in conformity with existing International and Human Rights Law.

Accessed on 2-28-17

Research on DU remediation:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304389413005694

Abstract

Contamination of soils with depleted uranium (DU) from munitions firing occurs in conflict zones and at test firing sites. This study reports the development of a chemical extraction methodology for remediation of soils contaminated with particulate DU. Uranium phases in soils from two sites at a UK firing range, MOD Eskmeals, were characterised by electron microscopy and sequential extraction. Uranium rich particles with characteristic spherical morphologies were observed in soils, consistent with other instances of DU munitions contamination. Batch extraction efficiencies for aqueous ammonium bicarbonate (42–50% total DU extracted), citric acid (30–42% total DU) and sulphuric acid (13–19% total DU) were evaluated. Characterisation of residues from bicarbonate-treated soils by synchrotron microfocus X-ray diffraction and X-ray absorption spectroscopy revealed partially leached U(IV)-oxide particles and some secondary uranyl-carbonate phases. Based on these data, a multi-stage extraction scheme was developed utilising leaching in ammonium bicarbonate followed by citric acid to dissolve secondary carbonate species. Site specific U extraction was improved to 68–87% total U by the application of this methodology, potentially providing a route to efficient DU decontamination using low cost, environmentally compatible reagents.

Another special report from the UN-Environmental Programme, did extensive studies and found that the penetrators from DU bombs were of concern, but found less evidence that there was widespread contamination in soil and water samples around the bomb impact zones.

http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/duserbiamont.pdf

Articles on Agent Orange:

http://www.agentorangerecord.com/impact_on_vietnam/environment/

http://www.agentorangerecord.com/information/what_is_dioxin/

Accessed on 3-21-17: https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports98/bosniacw/

Chemical Warfare in Bosnia? by Human Rights Watch

CIA use of toxins in SE Asia and Afghanistan:

https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000284013.pdf

Libby, Montana asbestos poisoning: http://www.pbs.org/pov/libbymontana/